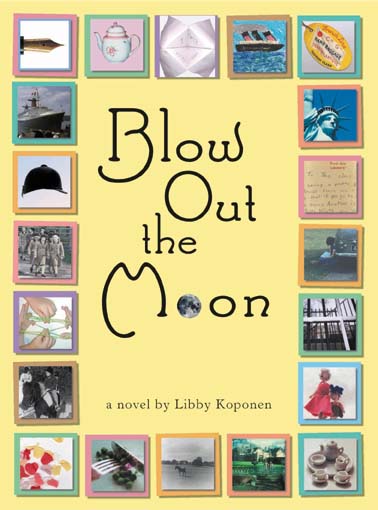

| My

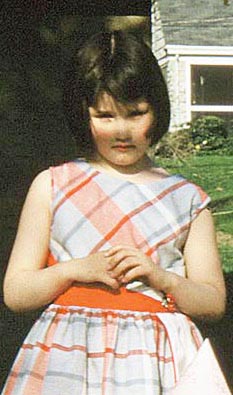

name is Libby Koponen and when I was a child, I was a tomboy. Some people

call me Lib ó in the book Iíll be “I” or “me,” except

when someone else is talking, because I am telling you this story. Itís

about the most interesting parts of my childhood. If you read it, youíll

figure out what I was like ó Iíll just say now that when my friends and

I got caught doing something a mother usually said: “I suppose you were the ringleader, Libby?” I thought of this as a compliment. It wasnít meant to be one, I know, but the word made me think of the circus and being in the center of all the excitement and fun. Thatís how I hope youíll think of this book. The story starts in America during summer vacation. We were playing outside at Kennyís house: Kenny (of course), my sister Emmy, Peg and Pat, and I. Peg and Pat are twins. I like to know what people in books look like, but I hate illustrations in long books ó they never show the people the way I imagine them. Iíll describe us all now, so you can picture us in your mind as youíre reading if you want to. Iím the main character, so Iíll start with myself. My hair is as straight as hair can be, and itís cut in a straight line across my forehead and straight along the sides, like the Dutch boy on the paint can. In pictures, my eyes look straight at the camera; theyíre blue. Iím short for my age, but Iím strong. I am not the kind of child grown-ups ever call “cute” or “just darling.” |

|

| Emmy,

my sister, can be that kind of child. She likes to sit on grown-upsí laps,

and she also likes to sleep in the same bed with me and snuggle, which

I hate. She smiles a lot and she fake-cries a lot, too. Her hair curls

and itís blonde. We do not look like sisters.

The twins look even less like sisters than Emmy and I do ó at least our eyes are the same color. Patís eyes are dark brown and her eyelashes are long and shiny and black, like her hair; she kind of peeks through them when she looks at people. Her face always looks clean, even when weíve been playing outside all day ó not like ours (I once heard my mother say, sighing, to another mother, “My children all have that pinky-white skin that looks dirty so quickly”). Patís hair never looks messy ó no matter what we do, it stays shining and in place. Patís good at making things and (although usually sheís sensible), she makes me laugh sometimes. When Emmy and I get in a fight Pat sings: “Sisterly love, sisterly love.” If any of the rest of us are fighting, she sings, “Neighborly love, neighborly love.” Pat and Kenny are in the same class at school. Peg is nothing like Pat. Pegís a tomboy (Patís kind of girlish and Kenny once said “Patís the quiet type at school” ). Pegís skinny and fast and her hair is almost as short as a boyís; it curls all over the place. Peg is good at sports and is the best coordinated of all of us. She loves their dog, Duke. Grown-ups say that Pat is going to be beautiful when she grows up; they never say that about Peg. Kenny is skinny, but strong ó not as strong as I am, but strong. He hates to sit still and he laughs and shouts a lot ó his front teeth are a little too big; but when he smiles, you notice his eyes, which are blue, more than his teeth and he has one dimple (in his chin). He tries to be funny too much, though. Kenny, Peg, and Pat are all taller than I am, but Iím the strongest of all of us ó and of everyone in my class at school, too; everyone Iíve wrestled, that is. Anyway we were at Kennyís, playing outside. We went in to get some Kool-aid; Mrs.Paley wasnít home, which was why we were playing over there, instead of at our house, which has a better yard. “Sheís hidden the Kool-aid in a new place,” Kenny said, “but donít worry, I know where it is.” He got up on the kitchen counter and told us to hand him the giant Saltine tin; he said it would be solid enough to stand on if two people held it. “I will,” Peg said. “Hold it the tall way. And hold it TIGHT. Lib, help her,” he said. So Peg held one side and I held the other and he got up on it and gripped a shelf; with the other hand he felt along the top of the cupboard. “Iíve got it!” he shouted and waved the packet at us. “Catch! Libby, donít let go.” Peg caught it; I held onto the Saltine

tin with both hands, and Kenny spread out his arms, screamed He landed with a huge thud. Peg handed the Kool-aid to Pat. Pat is always the one who makes the Kool-aid. Pat is kind of plump, though when we weigh ourselves, she always says she has big bones. Itís true that her hands are big. “Sheís hidden the sugar, too,” Pat said. “At least, itís not where it was last time.” So we all looked for it while Pat got out the big glass pitcher and the other things she needed and finally Emmy ó sheís really good at finding things ó pulled a new five pound bag out from under the sink. She heaved it up onto the table and we all looked at it. “Maybe she wonít notice,” I said. “She always notices ó but if we cut it with scissors and then are careful not to spill it all over the floor, she wonít really mind,” Kenny said, finally. “Iíll do everything in the sink,” Pat said. “That way, we can just rinse any mess down the drain.” Some people think this chapter is too long -- if you do: |

Peg. If

you changed your mind and DO want to read the descriptions, click

Kenny.

|

| She

poured the Kool-aid into the pitcher and started measuring the sugar while

we all stood around waiting and watching. Then Kenny got out the ice and

threw it at us ó Kenny always likes to be DOING something; it almost seems

as if he doesnít care what, as long as heís moving. He tried to drop some

ice down my neck but I grabbed it away and kicked it across the floor.

Kenny and Peg both ran after it and we all started kicking it as though

we were playing soccer. Pat went on stirring the Kool-aid. Then Kenny

held a whole tray of ice over the pitcher.

“No, donít!” Pat said, but too late ó he dumped it all in at once and a lot of Kool-aid splashed out. “Kenny!” Pat said. She doesnít like him as much as Peg and I do. “Itís only a few drops,” he said. “We can always make more.” Pat shook her head and her hair moved neatly, all in one piece. Her hair is always shining and perfectly neat; even her PART is always straight. Then she carried the Kool-aid to the table, and we arranged the glasses around it in a circle the way they are on TV ó the pitcher was already all foggy. Then, finally, we held out our glasses and carefully, without spilling one drop (except at the very beginning when some ice plopped out), Pat poured Kool-aid into them. It was Wild Cherry, our favorite; I like all the Kool-aid flavors except Lime, but Wild Cherry is the best. Then we went into the living-room and Kenny started banging on the piano ó not playing, just banging with his fists on the black and white notes at the same time. Peg did it, too ó he was banging on the really low notes and she was banging on the really high notes. “Iíve got a great idea!” I said. “Letís turn on everything in the house that can make noise, and scream our loudest, and see HOW MUCH noise we can make.” Sometimes people argue with my ideas,

but everyone could see right away that this was a really good one. Emmy

screamed: “Wait!” I said, and turned off the TV. “Letís not spoil it by turning things on one by one ó letís get all the stuff first. Then weíll turn it on and start screaming and yelling and jumping up and down all at once. That way, weíll get the full effect.” “But what else can we get?” Peg said. “The lawn mower.” Pat thought of that; she has pretty good ideas sometimes. “Perfect!” I said. “And we can bang pots and pans and their lids together.” Kenny didnít want to go get the lawnmower (he said it was “all the way” in the garage), and Pat and I were trying to convince him that we really needed it when we heard our bell ringing. Our parents have different ways of calling us: Peg and Patís bang a triangle like the ones they clang out West on ranches when they yell “Chow time!” Kennyís mother blows a whistle, and our parents ring a bell. They all have the same rule: when we hear it, we have to come right home ó no matter what weíre doing. If we donít, we have to stay in our own yard all the next day. “Oh, no,” I said. “What TERRIBLE timing.” Kenny didnít look sad at all and I could tell just what he was thinking. “You still have to get the lawnmower,” I said. “Have to?” he said, with a little smile. It took awhile to settle this (Iím not going to put in what we say in all our little arguments ó that would take too long and be too boring); Iíll just say that finally he DID agree to get it. “And youíll wait for us? You wonít start until we get back?” I said. “Weíll do it when we have all the stuff AND when you come back,” Kenny said. “But that wonít be the same!” Emmy said. “No, it wonít,” I said. “And it was my idea ó you canít do it without me.” The bell rang again; we had to leave. Pat said they WOULD wait and as we left, I heard her arguing and Kenny saying, “Come on, come on, letís get on with the game.” Kenny always says this ó he said it the time I slit my knee open playing running bases (the cut was so big that I had to go to the hospital for stitches). First Kenny said, without even looking at the cut, “Itís only a scratch, come on, Lib, get on with the game.” So I did, and then he looked and when he saw all the blood he screamed for his mother. When we got home, our mother was waiting for the guests: an English boy and his mother who were coming over for tea. We always have to play with our parents guestsí children, even if we donít know them or like them. Weíd never met this boy before ó he and his parents were from England. His father had been transferred from the London office of J. Walter Thompson ó thatís the company my father works for. Everything was all set up on the living-room table: a pewter tray with a round pewter tea pot and cream pitcher, a fat silver sugar bowl filled with sugar lumps ó you take them out with silver tongs. There were two plates of cookies (three different kinds: chocolate fingers, ginger snaps, and oatmeal), and one plate of little sandwiches cut into triangles. We washed and she inspected us and then she told us how many cookies we could each have (three) and reminded us to pass things to the guests first. One good thing about our mother is that she never corrects our manners in front of other people. I wish everyoneís mother would do this, I hate it when parents say things like “What do you say?” or scold their children in front of you. “Can I have one now?” Emmy said. She made a cute face but my mother still said no (I knew she would). “How many sandwiches?” I said. “You can try one of each kind, but I donít think youíll like them,” she said. “The brown ones are watercress and the white ones are shrimp.” Then the doorbell rang and we all ( Emmy, and our little sister, Bubby, and our little brother, Willy, and I) ran to the front door. I got there first. The mothers introduced themselves and said ladylike things like, “Please call me Isobel,” and my mother said to call her Sally. Then Mrs.Grant said, “And this is my son Neil.” My mother said hello, and he did, and then she put her arm around my shoulders and said, “This is my oldest daughter, Elizabeth.” I hate the name Elizabeth and she knows it ó I just gave her one look and she said, “But we always call her Libby.” She squeezed my shoulders and sort of pushed me towards them; I knew she wanted me to say hello politely so I did. Emmy did, too, but Bubby just stood behind my mother and so did our little brother. Then we all sat down and the mothers talked. We looked at Neil and he looked at us. Everything about him was light. His hair was yellow-white ó more white than yellow ó and his skin was pink and white, and his eyes were light blue and the whites were very white. He had bangs, which most boys donít. Kenny and most of the boys in my class have crewcuts. He ate slowly and carefully, wiping his mouth after every bite. He sat up very straight ó even his clothes were very straight ó and he didnít spill anything, even his tea. He seemed like a real goody-goody. The mothers talked about London and

my mother asked a lot of questions about “day schools for girls”

and Mrs. Grant answered and Mrs. Grant asked questions about “the

free schools here” and my mother answered; I didnít really listen

until Mrs.Grant said, Later they talked about silver ó that was interesting when my mother told about Paul Revere (the one in the Revolution) and when that was over I stopped listening and had more tea. For my second cup, she only put a few drops of tea ó the rest was milk. I added three lumps of sugar and stirred it. Youíd think that would be good ó I thought it would taste like a vanilla milkshake ó but sugar milk is a terrible combination, especially at the bottom of the cup. Iíd already had my three cookies, so I asked if I could be excused and she said Emmy and I could take Neil upstairs. That really meant that we could only go if we brought him with us. On the way up, I said, “Itís lucky that you or your mother didnít pour the tea.” “Why?” “Because youíre English and weíre American. If youíd given me a cup of tea, Iíd have had to dump it out ó in honor of the Boston Tea Party.” I was about to tell him what the Boston Tea Party was when he said: “Rubbish.” I was too surprised to say anything. Then he said: “My mother has given tea to lots of Americans before and THEY never poured it on the floor.” “Well, maybe other people donít do it but itís what I would do if an English person offered ME tea,” I said. Pouring the tea on the floor WOULD be like the Boston Tea Party. In case you havenít heard of it: In Boston, at the beginning of the Revolution, a crowd of grown-ups disguised as Indians sneaked onto an English ship and dumped all the tea into the Boston harbor. I think itís neat that our country had such a fun start ó grown-ups dressing up like Indians and throwing things overboard! And I like the name The Boston Tea Party, too. I didnít say any of this to Neil, though. We brought him into our room and he stood in the middle of it, with his back very straight, turning his chin around and looking at everything coolly. “This is our room,” Emmy said and brought him one of her horses. “This is my best gun,” I said. I buckled on the holster and drew, fast. “Itís a six-shooter,” I said, and stuck it back in the holster. “It can shoot more than six caps at a time, though.” “Sometimes we put caps on a rock and smash them with another rock,” Emmy said. “It makes a bigger noise.” Then I remembered. “Emmy! Making the noise!” Emmy and I looked at each other, and then we looked at Neil ó we knew we wouldnít be allowed to go without him. “Would you like to come with us to do something really fun?” I said. “What?” he said. I told him ó halfway through, he smiled and when he smiled he didnít look like such a goody-goody; it was kind of a mischievous smile. And at the end, he said: “That DOES sound fun.” “Good. Letís go!” I said. I tugged my holster around my hips the way the cowboys do when they swagger out the saloon doors into the street and led the way downstairs. The two mothers were still just sitting

on the couch, talking. Thatís all my mother ever does when her friends

come over ó when I ask her what they talk about, she says I asked if we could go to Kennyís to finish something and she and Mrs. Grant looked at each other. I wondered if they were about to use the secret code or signals or whatever it is that ladies use to tell each other things privately. I know they have one. I figured that out once when I was

at a friendís house and couldnít get out of my snowsuit in time to go

to the bathroom. I hope you donít think thatís gross, it was when I

was almost a baby, but, I admit, too old to be wetting my pants. Luckily,

you couldnít see the wet pants through the snowsuit. I called my mother

and asked her to come get me. The girl and her mother kept asking me

to stay until the end of the day and each time, I said: “No, I

want to go home.” When my mother got there, she and the girlís

mother stood at the front door, talking. I stood right next to them

the whole time and I listened to every word my mother said (I had asked

her on the phone not to tell about the wet pants) and she didnít say

anything about it, but at the end, the other mother said, I don't know if my mother and Mrs.Grant

used one. They looked at each other. Then my mother said that it was

on the same side of the street and that Kenny was “a nice boy.”

Mrs.Grant said something I didnít hear, and then our mother said that

we could stay for half an hour: Mrs.Grant said, We ran up to Kennyís. Peg was riding on Kennyís back, and Pat was running beside them, tossing her headó they were playing cowboys, as well as they could without us. (When we play that, Pat and Kenny are the horses, since theyíre the biggest, and Peg and I are Spin and Jess, the two bachelor cowboys. Emmy is usually a little colt.) Peg jumped off Kennyís back and they ran up to us; everyone stared at Neil. I said that he was English and had just moved into the Osborneís house. “And this is The Gang,” I said. “What is The Gang?” Neil said ó not suspiciously, just kind of eagerly, as though he thought it was going to be exciting. “Is it a club?” “Kind of,” I said. “What is it for? What do you do?” We all looked at each other and no one said anything. I thought saying “We play” would be disappointing, though that IS what we usually do. The Gang isnít really for anything: weíve just known each other since we were little and weíre always together, except at school. Finally, I said: “We have adventures.” Pat laughed. “And today is the Adventure of the Very Loud Living-Room,” she said. “Did you wait for us?” “Yes, we made him, and everythingís all ready,” Pat said. “We found everything we talked about, and then we thought of more.” We ran in. The lawn mower was in the middle of the room, and Jillís record player and the radio from the kitchen were on top of a small table. The lamp that usually is there was on the floor, unplugged. The pots and pans and lids were in a tidy little pile on the couch; as Pat said, there were two for everyone, if one person played the piano instead of banging pots. The blender was on the piano stool. Neil stood very still in the middle of the room, and then he turned around slowly, smiling at everything. “This is GREAT,” he said. “Wait until you hear it,” Kenny said. “Letís turn all the things on and start screaming at EXACTLY the same time,” I said. “Kenny, you do the TV, and Pat, the record player, and Peg the radio ó who knows how to work the lawn mower?” “I do,” Neil said. “Iíll do that.” “Good. And Emmy can do the blender and Iíll do the vacuum cleaner ó we can all grab pots and lids when everything is on. Take your places!” Everyone ran to the things they were supposed to turn on. “Iíll wait until everyoneís hand is on the switch, then Iíll count,” I said. “Ready?” Everyone nodded. “One, two, three, GO!” Everything CRASHED on at top volume:

the lawn mower, the TV, the radio, the record player, the blender, the

vacuum cleaner, but by the FAR the loudest noise was all of us screaming.

We didnít scream words, we just yelled: Kenny and Peg pounded the piano with their fists, jumping up and down as they banged. Emmy and Pat and Neil and I hit pots and pans together as hard as we could, screaming and jumping up and down the whole time. Our mouths were open as wide as they could go, and everyoneís faces turned red, even Patís. I donít know when Iíve had so much fun ó sometimes, I had to stop screaming to laugh. Peg and Kenny looked especially funny, jumping up and down at the piano. Kenny was wiggling his bottom in time to the music and shaking his head like a beatnik drum player. Then I saw Mrs.Paley in the doorway. She was holding a pocketbook and staring at all of us as if she wasnít sure who we were. Suddenly she jumped into the room, YANKED Kenny away from the piano, and shouted at him. He stopped screaming, of course; we all did. I turned off the vacuum and Pat got the radio and the record player. Emmy and Peg put their pots back on the couch. Neil just stood there, holding his ó he looked really scared. Our mother never shouts and his mother didnít seem like that type, either; I didnít blame Neil for being scared ó the first few times I saw Mrs. Paley having one of these fits, I was. “Kenneth! What the ___ are you doing? Turn that thing off!” she yelled. Kenny ran over to the lawnmower but he didnít know what to do, I could tell. “NOW!” she yelled and then she jabbed Kenny in the back and he bent over, but the lawnmower stayed on and Mrs.Paley yelled, “Hurry up!” Then, like a bugle boy dashing into the middle of a battle to help a wounded soldier, Neil darted in (I think that was brave of him) and pulled a long string. The lawnmower sputtered and gurgled off. Mrs.Paley whirled around. “Whoís he?” she yelled, waving her long arms ó Neil jumped away from her and landed on the lamp, which broke noisily. (First there was a kind of high crack, and then smaller crunches.) “This is the limit! I donít even know him and heís smashing my furniture! And what is the lawnmower doing in the living-room? Look at those spots!” We looked ó there was a trail of black splotches, sort of like the ones on the plastic sheet Jill uses to teach herself dance steps, going from the door to the lawnmower. She went on screaming. I remember: “My rug! Did any of you ever think about that?” and “Your mother doesnít let everyone play inside at her house! Why donít you go wreck everything there?” and, “I suppose you were the ringleader, Libby?” None of us said anything. At the end,

she said she was going upstairs and when she came back down, she wanted

everything back in its place and all of us out of the house: But Kenny didnít seem to mind; as we

left (we didnít talk at all while we put stuff away), he whispered to

Neil: “Donít worry, I can handle her.” When we were out of the Paleysí yard,

Neil said eagerly: “Oh, nothing,” I said. “Probably nothing,” Pat said. “Sometimes she does call our mothers. I think we should go home and tell first, just in case.” So we did. When we went in, the two mothers were still sitting in the same places, still talking. “Youíre back early,” my mother said. “What happened?” She knew nothing good had, I could tell. “We were doing something inside at Kennyís and some oil from the lawnmower spilled on the living-room rug. Also a lamp got broken,” I said. “Who broke the lamp?” she said. “It was an accident,” I said. “I did,” Neil said at the same time. Neilís mother, who had been drinking tea and staring out the window, kind of choked into her cup. But all she said was, “Thatís not like you, Neil.” Then she looked at me, probably thinking what most mothers think: that Iím a “bad influence.” My mother asked how oil from the lawnmower got on the rug, and I said I didnít know (well, I didnít: I wasnít there when they brought it in). My mother sighed, and said (to Mrs.Grant): “I hate to do it, but I think Iíll have to call Ruth Paley and assess the damage.” I think they talked in the secret lady way after that; I didnít understand what they were saying ó it was about Mrs.Paley, I think. When theyíd finished, my mother said: “And you children have been very naughty. Iím going to give you a punishment.” (This is something she hardly ever does ó all the kids from school who have come over say they wish my mother were our teacher, because sheíd always be saying: “Iíll give you one more chance.”) “What?” I said. I hate waiting for punishments. “Iíll think about it,” she said. “Part of it will be apologizing to Mrs. Paley.” “You mean go up there and say weíre sorry?” I did not want to go up there. But I didnít try to look cute ó I never do ó I just said: “Couldnít we write a letter and all three sign it?” Our mother looked at me, trying to decide; then Emmy said, “Iím scared to go there.” Only she didnít pronounce the r ó in front of other people she says her rís like wís but never when itís just her and me, she knows I canít stand it. Then she clasped her hands together, like the idiot on the cover of Prayers for Boys and Girls (a terrible book our grandmother gave us) ó and looked up at my mother. My mother sort of sighed and looked as though she might say yes after all. “If we wrote a letter, you could both read it before we sent it,” Neil said. “So can we?” I said. The two mothers looked at each other. “Well, yes, I suppose so,” our mother said. Writing the letter was kind of fun. Emmy drew a picture of the lamp shattering under a foot (and then she wrote BAD in big letters at the top). Neil had good handwriting and a lot of good ideas. He thought of beginning the letter with, “Dear Madam” and he also thought of putting, “We humbly beg your forgiveness.” He wanted us to sign it “Your humble servants,” but I explained that in America, we donít believe in servants (itís one of the things the Revolution was fought for, in a way), so we signed it plain From, and then our full names. When it was time to go home, Neil said: “Will you have another adventure tomorrow? Can I be in it?” So it really WAS an adventure ó at least, to him. |

Libby@ifyoulovetoread.com

Skip the prequel and go the real book

|

| Go

to the next chapter of the prequel (about the play we put on)

Go back to the list of chapters and stories

Skip the rest of the prequel and go the published book

|

|

The published book ismore about the boarding school in England. You can get it at the library, invite me to come to your school (my favorite!), order it from amazon, or buy it in bookstores. If you don't see it in a bookstore, please ask them to get it! If you DO see it, PLEASE TURN IT FACE OUT SO OTHER PEOPLE WILL SEE IT AND BUY IT. Thank you.